Joan Baez on her paintings of “Mischief Makers”

Source: CBS News / www.cbsnews.com / By Joan Blackstone /

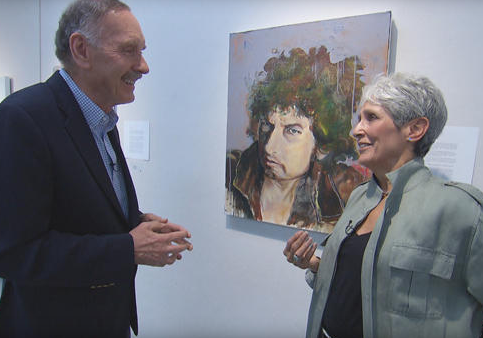

Joan Baez has long been recognized for her soulful voice. But at 77, she is also being recognized for another talent: painting.

Last fall acrylic portraits by her were shown in an exhibition at the in Mill Valley, Calif. Titled “Mischief Makers,” the show featured Baez’s depictions of activists, civil rights leaders, artists and others who have fought oppression and injustice.

In this extended transcript, “Sunday Morning” correspondent John Blackstone toured the exhibit with Baez, who discussed her history with many of her subjects and their propensity for causing mischief, as well as her own history in that area.

JOAN BLACKSTONE: So, these are all people that you call “mischief makers?”

JOAN BAEZ: People who have made social change through everything except violence: imagination, courage, nonviolent actions, civil disobedience, ended up in prison, risk-takers. And what people don’t know about them is, in their deathly serious, risk-taking work that they do, there is this side that keeps everything buoyed up, which is nonsense, puns, joking, general silliness, and mischief-making with the opponent to keep ’em off-guard. All the tools you need to make nonviolent change, you know?

BLACKSTONE: Just talking to you, I’m learning you have more mischief than I might’ve imagined.

BAEZ: Oh, God, I hope so. (LAUGHTER)

BLACKSTONE: So what was the inspiration for this entire show?

BAEZ: Trump. (LAUGHTER)

BLACKSTONE: Simple as that?

BAEZ: It’s the only good thing I have to say about (LAUGHTER) that bastard, was that I wouldn’t have had this focus if I hadn’t been inspired by — it’s really evil. And so what’s the antithesis that I have to offer against that darkness and evil, which covers the land at the moment? So, I guess I was hoping these personalities and what they’ve done in the world would shine through.

BLACKSTONE: Still a resistor, after all these years?

BAEZ: I hope so. (LAUGHTER)

BLACKSTONE: And so as you chose them, they’re all people who you know?

BAEZ: Almost all of ’em. There are a couple I hadn’t met, but most of ’em, yeah. They’ve been friends.

BAEZ: It was about three months before the Velvet Revolution really happened, and he came to the hotel. We were expecting [him but] didn’t know if he’d be arrested on the way, so when finally the phone rang, I said, “Yes?” He says, “Havel in lobby. Very many police.”

So I said “Come up.” And then he said, “Let’s plan mischief for government.” (LAUGHTER) So, we did everything we could. It was a nationally televised concert. We managed to get him in the public, sitting up where it would be really difficult for him to be arrested.

And at a moment in the evening, I said, in Czech, “And now I’d like to introduce my good friend, Vaclav Havel.” Audience exploded in excitement. The TV cut off. (LAUGHTER) And I sang “Swing Low” to him without a microphone, and that was when we bonded. And then he would say, “Mm, can think of more mischief!” (LAUGHTER) He was always looking for more mischief.

BLACKSTONE: Now all of these, when I look at the dates, 2016 and 2017? Did you paint them that quickly?

BAEZ: (LAUGH) Once I figured out a theme, I painted them very quickly. I think there are two or three that were done maybe three or four years ago, and honestly, if Trump hadn’t come on the scene, I wouldn’t have had as strong a theme. But I thought, “Oh, I’m gonna have a show. Let’s see. I could do this, I could do that. I could do musicians.” And then I thought, “No.” I mean, in the face of this disaster — you know, empathy’s gone, compassion is gone, kindness is gone — how can I say something in my art?

And it was very clear that the people who did live their lives, make social change, have an enormous influence on the world and do it out of love, beauty, caring — all the opposite things from the darkness — that this was just the simple no-brainer, to start painting these people, mostly whom I know. I’ve had the pleasure and good luck of knowing them.

BLACKSTONE: Many wouldn’t think of Martin Luther King as a mischief maker?

BAEZ: Dr. King was a mischief maker. And no, I think he had to be so careful on camera, to be serious, because anything that he might’ve said was an excuse to cut him down. So whatever humorous stuff he had to share was with smaller group and not in front of a microphone. And so the best mischief story with Dr. King was, I was allowed to go with his lieutenants to the airport to pick him up, to bring him to Grenada, Miss., to plan a march for the following day. So, I picked him up at the airport. I thought, “I’m gonna find out how these guys plan a march.” And they started telling jokes, and they told jokes from the airport to his favorite restaurant, where he ate everything that you would imagine that he would eat.

It was a joke! I mean, it was fried chicken, potatoes, okra, apple pie for dessert. Got back in the car, and I thought, “Well, now I’m gonna hear how they plan a march.” Told jokes all the way back to the [conference]. And I asked Andy Young that night, I said, “I thought I was gonna hear from you guys how you plan a march?” He said, “You did!” (LAUGHTER)

BLACKSTONE: So they were fighting for justice, but having fun along the way somehow?

BAEZ: There you go. Yeah.

BLACKSTONE: So the other paintings here, there’s lots of color. This is black and white?

BLACKSTONE: Is it an escape when you’re painting? I mean, are you thinking all the time when you’re painting, or does it just kind of happen like that?

BAEZ: Oh, it happens. It’s not always easy. Sometimes more difficult than other times. But I listen to podcasts. I listen to popular music. I listen to nothing. I do a lot of work just in silence. We have a lot of birds and things around the property, and that seems to be enough. (LAUGHS)

BAEZ: Marilyn Youngbird is a close friend of mine. She’s been our medicine woman, done sweat lodges with myself and my friends. My son introduced me to all of the Native American healing ceremonies, and that’s how I got to know Marilyn. And eventually, a couple of years ago, I was inducted into her family, the Youngbird family, and tribe, which is the Hidatsa Mandan tribe, and given a name, Sacred Voice Eagle Woman. You couldn’t get any dandier than that, really, you know?

Anyway, the whole story about this exhibit really stems from my relationship with Marilyn and her relationship with the man who’s the chairman of a tribe nearby. And he owns and runs a casino. There’s lots and lots and lots of money. He knows casino owners, who have lots and lots and lots of money, and I called him to say, “Well, I’ll give you a heads up, if you want to get the Marilyn picture.”

And he said, “Don’t sell anything else. I’m on my way to a tribal council meeting. I think they’re gonna wanna buy everything.” And they did! It was a unanimous vote to donate to Sonoma State University Cultural Justice Center.

BLACKSTONE: So, these paintings will be on display in the Social Justice Center, and free to be shown in other places?

BAEZ: That’s right, yeah.

BLACKSTONE: Social justice for many years has been your calling? More than music, even?

BAEZ: Well, it’s juggled. I’d have to figure which one was more important than the other, but the fact is that I do them best when I’m doing them together. It’s always been that way with the singing. And my guess is from this first show, that’s how it’ll be with the painting, that it has something educational to offer, something to do with activism, with nonviolence, and now with trying to return to empathy, which has almost been wiped off the map. [We] struggle ahead, and I’m happy to be able to do part of it, anyway, in painting.

BLACKSTONE: When did you begin painting?

BAEZ: I’ve sketched my whole life, from when I was five. (LAUGHS) And done cartoons and done lookalikes when I was 15, I sold portraits of Jimmy Dean for $5. I think I was in third grade, I sold pictures of Bugs Bunny for three cents (LAUGHTER). But the more serious, getting into acrylics, that was six years ago, I started.

BLACKSTONE: I think you’ve said that your voice was a gift? This is another gift?

BAEZ: It is, yeah.

BLACKSTONE: How are you so lucky?

BAEZ: I don’t know. (LAUGHTER) I don’t know, but I am! (LAUGHTER)

BLACKSTONE: And using that luck to try to help other causes, as well?

BAEZ: That makes it fulfilling. That’s what’s given my life meaning to me, and given it richness, has been not just the singing or not just the painting, but you know, going a little bit out of that circle and trying to influence the circle of good.

BLACKSTONE: Are there parallels between creating on canvas and creating on paper? Writing a song versus doing a painting?

BAEZ: Somebody asked me that the other day. I think they’re different. Eventually, sooner rather than later, [I’ll] quit the formal touring, which means that the timetable is very different. I won’t be getting on the bus for six weeks and doin’ the thing, coming back and recovering from that. That won’t be anymore. So, what I see in there is more time for painting, you know? It’s another career.

BLACKSTONE: You clearly need a creative outlet?

BAEZ: I don’t think I’d be happy without one.

BLACKSTONE: It’s beautiful, she’s beautiful. It’s a beautiful painting. Her eyes are captivating.

BAEZ: Yeah, well, they were, for real. Men would fall into those pools, you know, of blue and purple, and there was no retrieving them. (LAUGHTER) She created an organization that she ran for 25 years, Bread and Roses, taking music into institutions where people had nothing in the way of entertainment. And she did her organization in such a way that when she died, it continued, and it continues today.

BLACKSTONE: And certainly it’s a very valuable, treasured organization to many people. It doesn’t seem to fall into the social justice.

BAEZ: Yeah. Not officially. Neither is Dylan, you know? I mean, he wrote the music that was our background. He’s not a social activist. Mimi actually went to jail with me for supporting the draft resistance.

BLACKSTONE: And your mother, too, right? (LAUGH)

BAEZ: And my mother did, as well. So, it kind of runs in the family. (LAUGHTER)

BAEZ: My father’s parents were sort of missionaries. His father left the Catholic Church in Mexico, which is already rebellious. Became a Methodist minister. Was a missionary in Brooklyn for poor Puerto Rican families. My mother’s father was a plague to the DAR, because he was a leftwing activist in the United States. They came from Scotland. And so yeah, it’s in the blood.

And then my mother and father became Quaker when I was eight. My mother knew about Quakerism, and my father was looking for somewhere to worship, and we were trying all these churches. A kid’s not interested in churches, you know? And then the most boring of them all was Quaker. You just sit and be quiet. (LAUGHTER) There’s nothing even to look at, you know? So, of course we loathed it.

But I would say that the silence, the meditative silence that I was forced to sit through when I was a kid, actually in the end just stayed with me. And I’ve always been, you know, a meditator and appreciated that silence.

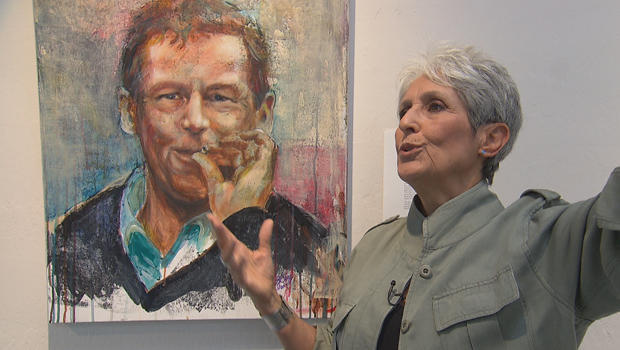

BAEZ: Old Happy Face. (LAUGHTER) Yeah. We called him Old Happy Face. Well, without Dylan, we really wouldn’t have had that kind of a movement. He was our strongest arsenal of music that we used, and still use for everything. There hasn’t been another Bob. There won’t be.

There’ll be people who write good songs, but he and I were a part of a ten-year explosion of talent and political activity and activism. Bob was not an activist; he didn’t need to be. He wrote us that music. If he’d written just “Blowing in the Wind,” it would’ve been enough, you know? But he just was prolific and somehow or other channeled, I don’t know what, but just wrote and wrote and wrote, and all of those songs were the greatest that we have.

Well, I think it kinda captures Bob. (LAUGH) He’s not a smiley type, you know? I just looked for what seemed to represent him. It was a cover of one of the books that we had to get an okay from.

BLACKSTONE: But that was a photograph? This is kind of a chaos (LAUGHTER) of color in here? And dare I say, eyes as blue as robin’s eggs?

BAEZ: You dare! (LAUGHTER) And that’s what they are.

BLACKSTONE: Was there emotion in painting this? Did this bring up emotion in ways?

BAEZ: Somewhat, but if I were to talk about emotion, I would say the picture of my ex-husband was something about it, so youthful and so like a chunk of my life, that one I wept through. That one, tears just kept coming. And in that way, no. I took this challenge to paint Bob, and I’ve had enough emotions about Bob! (LAUGHTER)

BLACKSTONE: So is this David as he was when you met him, basically?

BAEZ: Yeah, it is. I asked him to send his favorite picture, and it was this. And he’s just so youthful, he was 22. And he spent 20 months in prison for something that he really believed in.

And our marriage didn’t last, but just the expression on his face, a little bit of wonder and confusion, but knowing that this guy took his stand and did what he did, and the mischief story with him is just that when he was arrested, the sheriffs came to our house. And we invited them in, which is already (LAUGHTER) very confusing for them! And offered them coffee, which they refused.

And then they put handcuffs on David and put him in the back of the car, and all of our resistance, resist-the-draft people were there and our commune people and our anti-war people, and as the sheriff’s car drove off, somebody had stuck a “Resist the draft” (LAUGHTER) bumper sticker over the license plate. So, we were all cheering, (LAUGHTER) and that was our bit of Bay Area mischief.

And this [tattoo] also had had my name on it. And when I found that out, I went into another spasm of tears. It was something so moving about that. And I said, “David, what was on the tattoo?” And he said, “It said Joanie.” And so I burst into tears again. And I put it there, and I thought, “Nah, that’s too — it should just be David,” you know?

BLACKSTONE: In some ways, this looks unfinished. I mean, I think I can still see sketch marks —

BAEZ: Yeah, you can.

BLACKSTONE: — on there or something? (UNINTEL) Could you not bear to finish it?

BAEZ: Oh, no. It’s not that. But I learned how to draw glasses. I took a pencil. And I wet it, and I (LAUGHTER) it’s just all experimentation for me, yeah. I mean, the techniques are all experimentation.

BLACKSTONE: So, is this your favorite?

BAEZ: In some ways, this is. I wanted to keep it. I didn’t want to sell it. But then when it went as this wonderful group, I thought, “Well, he belongs with the rest of ’em, to be seen and learned about.”

BLACKSTONE: When he went to prison, you were pregnant?

BAEZ: Yeah. Six months pregnant. And I went on tour, and David went to jail. And I had Gabe, and we would go and visit David in prison. And it was not an easy time for him, ’cause they didn’t like these political people types in prisons, and they gave him a nasty time.

BLACKSTONE: Tough time for you, I would think as well.

BAEZ: Yeah. It was not a happy time. (LAUGH)

BLACKSTONE: But a sacrifice for the cause at that time?

BAEZ: Probably. I could put it that way, although I never thought in terms of sacrifice. It was kind of just my life, you know? It was a rough time period, and it was also a fulfilling time in my life. Of jail, of prison, I used to say, and I still do, “Anybody running for public office should’ve spent at least 48 hours in jail, to know what this …” You don’t know what a country is about until you’ve seen what goes on inside a prison.

BLACKSTONE: Let me start by asking, is it any different painting yourself than these others?

BAEZ: I don’t think so, although I will say I’ve tried some other ones and they haven’t (LAUGH) worked out.

BLACKSTONE: Some other self-portraits?

BAEZ: Yeah. So, maybe it is harder. This is about the fourth one I tried, and this is the first one I’ve liked. It has to do also that it was a magnificent photograph to begin with. It’s a Karsh photograph. So, it was right smack in the middle of a stained glass window in the photograph. Very dramatic, but I had short hair. And poor Karsh was just absolutely horrified to find out when he got the long distance up the hill to my little house, then I greeted him, he said, “Where’s your hair?”

And I said, “Well, I cut it off.” And it took him I don’t know how long to adjust to the fact that he’d have to do something that he hadn’t dreamed of before. So, at one point, he went looking around the garden, and he found some lilacs. And he brought the lilacs in, and here I was sitting very dramatically with a cape on, and he puts the lilacs over my hand, and they’re flopping on this way, and then they’re flopping on that way. And he said, “Oh, these lilacs. We need them to …” I said “Fall, you f***ing lilacs.” (LAUGHTER) We met on that level, briefly. He was a little snooty!

BLACKSTONE: So, your hair was short in the photograph–

BAEZ: Yeah, and then I just brought it back [in the painting]. It doesn’t take four years to to grow it out!

BLACKSTONE: So when you look at this woman now, who is she? Is she the same woman who’s standing here today?

BAEZ: You know, it’s a good question. It’s the same as listening to early music. And in some ways, I feel just disembodied. I mean, I don’t have the same voice. I don’t look the same. I admire that young woman who sang, who did those things, who was taking care of Gabe by herself. I mean, I was surrounded by people in a commune and friends, but David was in prison. And so I have a lot of admiration for whoever that was at that time, but it’s hard to feel like the same person now.

BLACKSTONE: Where did this fall in these paintings? Was it early in this series?

BAEZ: No, it was one of the very last ones I painted.

BLACKSTONE: Did you hesitate then to paint yourself?

BAEZ: No.

BLACKSTONE: So, describe yourself as a mischief maker? All your life?

BAEZ: Yeah. I would say all my life, mischief maker. I mean, I wouldn’t know really where to begin, to tell mischief stories of my own. I mean, from as small a thing as the cascading lilacs, I’ve always had a jocular sense. I just think if I didn’t have that humor, same as if King didn’t have that humor, you’d just die of seriousness. I mean, I think you have to be serious about what we’re doing, but we can’t take ourselves so seriously, or it’s just boring, you know? It’s not any use to anybody.

I think for years, I was so serious, and I was also afraid that people wouldn’t take me seriously if I joked. But also, I was just shy. I had this thing in front of the microphone, and people thought I was just composed and whatever. And I was wracked with stage fright, but I was able to pull it off from a very, very early age.

So when you ask when we think about mischief, there is so much of my life that is just mischief. (LAUGHTER)

I was 16, and we had an air raid drill, which meant that we were supposed to hide under our desks (LAUGHS) or go home. Our parents are supposed to come and get us, which is insane. We’re waiting for the missile to come from Moscow to Palo Alto High School! So I said, “This is nonsense,” and I stayed in school for this first civil disobedience I ever did.

I stayed in school, and they didn’t know what to do with me. And I was all perky, wanted to talk about missiles and anti-war and pacifism, and the secretaries down in the office had never engaged in such a conversation. The principal didn’t know what on Earth I was doing. He put me in the study hall, ’cause they didn’t know what else to do with me. There was one other person there, and it was a kid who refused to go home because he wanted to do his math. He says, “I got work to do here.” And (LAUGHS) it’s only the two of us in there. So, you know, part of that feels like mischief, and then part of it was just essential to my life.

It was the first official getting-in-trouble that I did. I mean, the next day, the papers had this story. The day after that, the papers had letters to the editors from the parents of the children at my school: “Watch out for this Communist.” (LAUGHTER) Seriously, that’s when that started.

BLACKSTONE: And that made you feel pretty good?

BAEZ: I didn’t know what a Communist was! (LAUGHTER) Honest to God, I didn’t. I thought, “Ooh, that must be somethin’ bad.” Honestly in some sense, it was really naïve. I certainly was naïve, until I decided I had to educate myself about all things political and all things nonviolent. Fell in love with Mahatma Gandhi’s work. Met Dr. King. Changed my life, and then the path was sort of inevitable from there on.

BAEZ: Ram Dass, spiritual leader, Buddhist. He was a sort of a regular person once, and then he eventually became … I saw him last year for the first time in maybe 15 years, and if I ever experienced a person that I thought, “Oh my God, this guy’s enlightened” — because I don’t really believe in that stuff, but he emanated light and love.

He had a stroke. He can’t even turn over in his bed at night now. And he smiles, and can’t talk very well, so I just held his hand. Cried. And I asked him some questions. You know, I said, “Do you have a lot of pain?” He said, “Yes.” (LAUGHTER) And I said, “What do you do with it?” “Well, I”– and he did this mechanical thing his brain, and he said, “And then I love it.”

So (LAUGH) he has embraced the pain. He’s loved the pain, as part of life. And it was way beyond me! I thought, “Ooh, maybe someday (LAUGHTER) I’ll be like that.” And at the same time, even in his joking, when he’s talking, he’s a mischief maker from way, way, way, back.

BLACKSTONE: The advantage of your music and your activism has given you the opportunity to be embraced by all these all these people? How does that feel, when you look around this room and say, “These are my friends”–

BAEZ: Ooh, I love it. I mean, I feel as though they’ve given me some kind of (LAUGH) status in life. I was at the right place at the right time, had the right voice, and the right intentions, at least for me, for my values. And part of that ten-year period that I mentioned, where the musicians were just overflowing with words and songs and gifts. And many of ’em, a willingness to take risks for the anti-war movement and for the civil rights movement. And I was there. You know, and I had the voice, and I’m grateful for that.

BAEZ: John Lewis. I mean, look at the resolve in this guy. As we all know, beaten up in the civil rights movement. Solidly nonviolent, and to this day he speaks of nonviolence and love. Mischief for me actually was when, I can’t remember the bill they were trying to pass or stop, but he got his fellow Congress people kneeling in Congress, on the floor, all these white folks! (LAUGHTER)

You know, I thought, “Man, that is so John Lewis.” And they had to. I mean, here he’s on his knees praying, and so they had to get on their knees and pray, too. Some people gave up wanting to talk about love, you know? But these guys, with all of his toughness and what he’s been through, to still talk about love and nonviolence is really important.

BLACKSTONE: Certainly, you know, in the last year we’ve had these clashes where there’s been violence and people saying certainly the way to fight against people who want you to get violent is to be nonviolent, is to fight them with humor? Are you hoping to spread that message, with this work?

BAEZ: Well, that’s been my business since I was 15. If you look carefully at nonviolent movements, fewer people are killed, fewer people die, and they’re more successful. It’s just so hard for people to wrap their heads around activism that’s — I mean, violence has been contagious since the beginning of time. It’s easier to organize violence than it is to organize nonviolence.

These people, and King, and Gandhi, who may be in the next group of mischief makers, understand it’s not just a moral issue, it’s a practical issue. If you want to really have a chance of survival and transcendence against the enemy, first of all, if it’s serious armaments, you have the brains to know you don’t have a chance.

The only chance you have is to appeal to the humanity, or to be clever enough to find ways to make your point. But if you pick up a gun, you’re finished. The public is no longer with you. You’ve sold your morality down the drain. And you’ve given up on empathy, humanity, all of that, which may be really hard to find in a group of Nazis. But I can tell you, the one thing that’s not gonna work for you, facing a bunch of Nazis, is to try and out-Nazi them, ’cause you can’t do it.

BLACKSTONE: And it seems you’re suggesting as well, don’t just meet them with nonviolence; meet them with humor? Meet them with mischief?

BAEZ: Meet them at mischief and humor, to the best of your abilities, as well. Humor may be the most disarming of all possible choices of what to do, the way Havel did. Havel, he had my guitar in his hand when we went into this auditorium, and the security was saying, “Oh, we’ll take that.” And he said, “No, no, I am roadie.” (LAUGHTER) “Road manager.” Everything he did was mischief, and at the same time, his leadership was about to topple the Communist government, and the humor was the best part of it all.

BLACKSTONE: We’ve talked about how you’ve known you’re a talented artist since you were a teenager? How is this different than singing?

BAEZ: Oh, that’s simple. The reason I will stop singing is that it’s too difficult. It takes tremendous effort to make sounds that I want to hear. I can do it, and I’ll make a beautiful album, and it’ll probably be my last, because the effort is too great.

This [painting] is effortless. I mean, I shouldn’t say that. There are times when it’s difficult, but it’s not the same kind of– I’m doing this because (UNINTEL) the vocal chords. They’re a muscle. They’re tired. You know, you have to keep working and working and working to get ’em to do what you want ’em to do.

So, it’s just a totally different feeling. This is more freeing right now. When I was young, the voice was free. It didn’t need anything. It didn’t need training. I didn’t need to know how to breathe, anything. And now it’s all smoke and mirrors and effort, whereas this is smoke and mirrors, but it’s not that difficult.